(This post is the fourth in a series about a spring-break field trip taken last week with my Barrier Islands class, which I teach in the Department of Environmental Studies at Emory University. The first three posts, in chronological order, tell about our visits to Cumberland Island, Jekyll Island, and Little St. Simons and St. Simons Islands. For the sake of conveying a sense of being in the field with the students, these posts mostly follow the format of a little bit of prose – mostly captions – and a lot of photos.)

When planning a week-long trip to the Georgia barrier islands with my students, I knew that one island – Sapelo – had to be included in our itinerary. Part of my determination for us to visit it was emotionally motivated, as Sapelo was my first barrier island, and you always remember your first. But Sapelo has much else to offer, and because of these many opportunities, it is my favorite as an destination for teaching students about the Georgia coast and its place in the history of science.

Getting to Sapelo Island requires a 15-minute ferry ride, all for the low-low price of $2.50. (It used to cost $1.00 and took 30 minutes. My, how times have changed.) For my students, their enthusiasm about visiting their fourth Georgia barrier island was clearly evident (with perhaps a few visible exceptions), although photobombing may count as a form of enthusiasm, too.

Getting to Sapelo Island requires a 15-minute ferry ride, all for the low-low price of $2.50. (It used to cost $1.00 and took 30 minutes. My, how times have changed.) For my students, their enthusiasm about visiting their fourth Georgia barrier island was clearly evident (with perhaps a few visible exceptions), although photobombing may count as a form of enthusiasm, too.

I first left my own traces on Sapelo in 1988 on a class field trip, when I was a graduate student in geology at the University of Georgia. My strongest memory from that trip was witnessing alligator predation of a cocker spaniel in one of the freshwater ponds there. (I suppose that’s another story for another day.) Yet I also recall Sapelo as a fine place to see geology and ecology intertwining, blending, and otherwise becoming indistinguishable from one another. This impression will likely last for the rest of my life, reinforced by subsequent visits to the island. This learning has always been enhanced whenever I’ve brought my own students there, which I have done nearly every year since 1997.

As a result of both teaching and research forays, I’ve spent more time on Sapelo than all of the other Georgia barrier islands combined. Moreover, it is not just my personal history that is pertinent, but also how Sapelo is the unofficial “birthplace” of modern ecology and neoichnology in North America. Lastly, Sapelo inspired most of the field stories I tell at the start of each chapter in my book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast. In short, Sapelo Island has been very, very good to me, and continues to give back something new every time I return to it.

So with all of that said, here’s to another learning experience on Sapelo with a new batch of students, even though it was only for a day, before moving on to the next island, St. Catherines.

(All photographs by Anthony Martin and taken on Sapelo Island.)

Next to the University of Georgia Marine Institute is a freshwater wetland, a remnant of an artificial pond created by original landowner R.J. Reynolds, Jr. More importantly, this habitat has been used and modified by alligators for at least as long as the pond has been around. For example, this trail winding through the wetland is almost assuredly made through habitual use by alligators, and not mammals like raccoons and deer, because, you know, alligators.

Next to the University of Georgia Marine Institute is a freshwater wetland, a remnant of an artificial pond created by original landowner R.J. Reynolds, Jr. More importantly, this habitat has been used and modified by alligators for at least as long as the pond has been around. For example, this trail winding through the wetland is almost assuredly made through habitual use by alligators, and not mammals like raccoons and deer, because, you know, alligators.

Photographic evidence that alligators, much like humans prone to wearing clown shoes, will use dens that are far too big for them. This den was along the edge of the ponded area of the wetland, and has been used by generations of alligators, which I have been seeing use it on-and-off since 1988.

Photographic evidence that alligators, much like humans prone to wearing clown shoes, will use dens that are far too big for them. This den was along the edge of the ponded area of the wetland, and has been used by generations of alligators, which I have been seeing use it on-and-off since 1988.

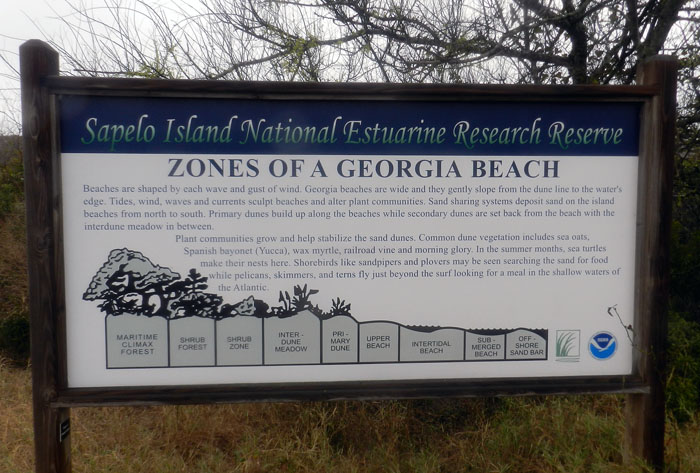

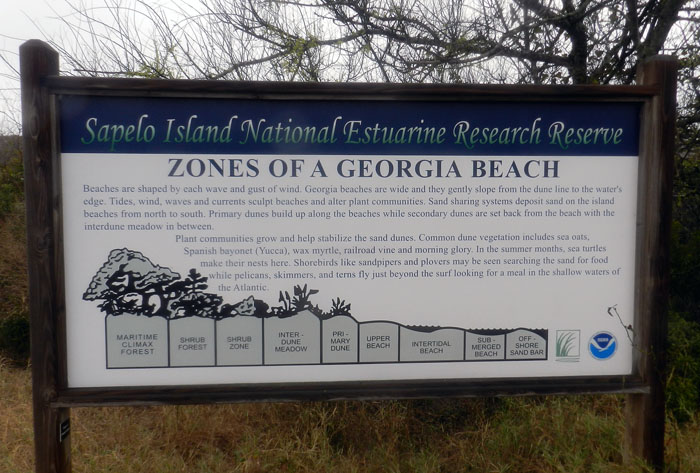

An idealized diagram of ecological zones on Sapelo Island, from maritime forest to the subtidal. This sign provided a good field test for my students, as they had already (supposedly) learned about these zones in class, but now could experience the real things for themselves. And yes, this will be on the exam.

An idealized diagram of ecological zones on Sapelo Island, from maritime forest to the subtidal. This sign provided a good field test for my students, as they had already (supposedly) learned about these zones in class, but now could experience the real things for themselves. And yes, this will be on the exam.

When it’s high tide in the salt marsh, marsh periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata) seek higher ground, er, leaves, to avoid predation by crabs, fish, and diamondback terrapins lurking in the water. Here they are on smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), and while there are getting in a meal by grazing on algae on the leaves.

When it’s high tide in the salt marsh, marsh periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata) seek higher ground, er, leaves, to avoid predation by crabs, fish, and diamondback terrapins lurking in the water. Here they are on smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), and while there are getting in a meal by grazing on algae on the leaves.

Erosion of a tidal creek bank caused salt cedars (which are actually junipers, Juniperus virginiana) to go for their first and last swim. I have watched this tidal creek migrate through the years, another reminder that even the interiors of barrier islands are always undergoing dynamic change.

Erosion of a tidal creek bank caused salt cedars (which are actually junipers, Juniperus virginiana) to go for their first and last swim. I have watched this tidal creek migrate through the years, another reminder that even the interiors of barrier islands are always undergoing dynamic change.

OK, I know what you’re thinking: where’s the ichnology? OK, how about these wide, shallow holes exposed in the sandflat at low tide? However tempted you might be to say “sauropod tracks,” these are more likely fish feeding traces, specifically of southern stingrays. Stingrays make these holes by shooting jets of water into the sand, which loosens it and reveals all of the yummy invertebrates that were hiding there, followed by the stingray chowing down. Notice that some wave ripples formed in the bottom of this structure, showing how this stingray fed here at high tide, before waves started affecting the bottom in a significant way.

OK, I know what you’re thinking: where’s the ichnology? OK, how about these wide, shallow holes exposed in the sandflat at low tide? However tempted you might be to say “sauropod tracks,” these are more likely fish feeding traces, specifically of southern stingrays. Stingrays make these holes by shooting jets of water into the sand, which loosens it and reveals all of the yummy invertebrates that were hiding there, followed by the stingray chowing down. Notice that some wave ripples formed in the bottom of this structure, showing how this stingray fed here at high tide, before waves started affecting the bottom in a significant way.

Here’s more ichnology for you, and even better, traces of shorebirds! I am fairly sure these are the double-probe beak marks of a least sandpiper, which may be backed up by the tracks associated with these (traveling from bottom to top of the photo). But I could be wrong, which has happened once or twice before. If so, an alternative tracemaker would be a sanderling, which also makes tracks similar in size and shape to a sandpiper, although they tend to probe a lot more in one place.

Here’s more ichnology for you, and even better, traces of shorebirds! I am fairly sure these are the double-probe beak marks of a least sandpiper, which may be backed up by the tracks associated with these (traveling from bottom to top of the photo). But I could be wrong, which has happened once or twice before. If so, an alternative tracemaker would be a sanderling, which also makes tracks similar in size and shape to a sandpiper, although they tend to probe a lot more in one place.

Just in case you can’t get enough ichnology, here’s the lower, eroded shaft of a ghost-shrimp burrow. Check out that burrow wall, reinforced by pellets. Nice fossilization potential, eh? This was a great example to show my students how trace fossils of these can be used as tools for showing where a shoreline was located in the geologic past. And sure enough, these trace fossils were used to identify ancient barrier islands on the Georgia coastal plain.

Just in case you can’t get enough ichnology, here’s the lower, eroded shaft of a ghost-shrimp burrow. Check out that burrow wall, reinforced by pellets. Nice fossilization potential, eh? This was a great example to show my students how trace fossils of these can be used as tools for showing where a shoreline was located in the geologic past. And sure enough, these trace fossils were used to identify ancient barrier islands on the Georgia coastal plain.

Understandably, my students got tired of living vicariously through various invertebrate and vertebrate tracemakers of Sapelo, and instead became their own tracemakers. Here they decided to more directly experience the intertidal sands and muds of Cabretta Beach at low tide by ambulating through them. Will their tracks make it into the fossil record? Hard to say, but I’ll bet the memories of their making them will last longer than any given class we’ve had indoors and on the Emory campus. (No offense to those other classes, but I mean, you’re competing with a beach.)

Understandably, my students got tired of living vicariously through various invertebrate and vertebrate tracemakers of Sapelo, and instead became their own tracemakers. Here they decided to more directly experience the intertidal sands and muds of Cabretta Beach at low tide by ambulating through them. Will their tracks make it into the fossil record? Hard to say, but I’ll bet the memories of their making them will last longer than any given class we’ve had indoors and on the Emory campus. (No offense to those other classes, but I mean, you’re competing with a beach.)

The north end of Cabretta Beach on Sapelo is eroding while other parts of the shoreline are building, and nothing screams “erosion!” as loudly as dead trees from a former maritime forest with their roots exposed on a beach. Also, from an ichnological perspective, the complex horizontal and vertical components of the roots on this dead pine tree could be compared to trace fossils from 40,000 year-old (Pleistocene) deposits on the island. Also note that at this point in the trip, my students had not yet tired of being “scale” in my photographs, which was a good thing for all.

The north end of Cabretta Beach on Sapelo is eroding while other parts of the shoreline are building, and nothing screams “erosion!” as loudly as dead trees from a former maritime forest with their roots exposed on a beach. Also, from an ichnological perspective, the complex horizontal and vertical components of the roots on this dead pine tree could be compared to trace fossils from 40,000 year-old (Pleistocene) deposits on the island. Also note that at this point in the trip, my students had not yet tired of being “scale” in my photographs, which was a good thing for all.

Another student eager about being scale in this view of a live-oak tree root system. See how this tree is dominated by horizontal roots? Now think about how trace fossils made by its roots will differ from those of a pine tree. But don’t think about it too long, because there are a few more photos for you to check out.

Another student eager about being scale in this view of a live-oak tree root system. See how this tree is dominated by horizontal roots? Now think about how trace fossils made by its roots will differ from those of a pine tree. But don’t think about it too long, because there are a few more photos for you to check out.

Told you so! Here’s a beautifully exposed, 500-year-old relict marsh, formerly buried but now eroding out of the beach. I’ve written about this marsh deposit and its educational value before, so will refrain from covering that ground again. Just go to this link to learn about that.

Told you so! Here’s a beautifully exposed, 500-year-old relict marsh, formerly buried but now eroding out of the beach. I’ve written about this marsh deposit and its educational value before, so will refrain from covering that ground again. Just go to this link to learn about that.

OK geologists, here’s a puzzler for you. The surface of this 500-year-old relict marsh, with its stubs of long-dead smooth cordgrass and in-place ribbed mussels (Guekensia demissa), also has very-much-live smooth cordgrass living in it and sending its roots down into that old mud. So if you found a mudstone with mussel shells and root traces in it, would you be able to tell the plants were from two generations and separated by 500 years? Yes, I know, arriving at an answer may require more beer.

OK geologists, here’s a puzzler for you. The surface of this 500-year-old relict marsh, with its stubs of long-dead smooth cordgrass and in-place ribbed mussels (Guekensia demissa), also has very-much-live smooth cordgrass living in it and sending its roots down into that old mud. So if you found a mudstone with mussel shells and root traces in it, would you be able to tell the plants were from two generations and separated by 500 years? Yes, I know, arriving at an answer may require more beer.

Although a little tough to see in this photo, my students and I, for the first time since I have gone to this relict marsh, were able to discern the division between the low marsh (right) and high marsh (left). Look for the white dots, which are old ribbed mussels, which live mostly in the high marsh, and not in the low marsh. Grain sizes and burrows were different on each part, too: the high marsh was sandier and had what looked like sand-fiddler crab burrows, whereas the low marsh was muddier and had mud-fiddler burrows. SCIENCE!

Although a little tough to see in this photo, my students and I, for the first time since I have gone to this relict marsh, were able to discern the division between the low marsh (right) and high marsh (left). Look for the white dots, which are old ribbed mussels, which live mostly in the high marsh, and not in the low marsh. Grain sizes and burrows were different on each part, too: the high marsh was sandier and had what looked like sand-fiddler crab burrows, whereas the low marsh was muddier and had mud-fiddler burrows. SCIENCE!

At the end of a great day in the field on Sapelo, it was time to do whatever was necessary to get back to our field vehicle, including (gasp!) getting wet. The back-dune meadows, which had been inundated by unusually high tides, presented a high risk that we might experience a temporary non-dry state for our phalanges, tarsals, and metatarsals. Fortunately, my students bravely waded through the water anyway, and sure enough, their feet eventually dried. I was so proud.

At the end of a great day in the field on Sapelo, it was time to do whatever was necessary to get back to our field vehicle, including (gasp!) getting wet. The back-dune meadows, which had been inundated by unusually high tides, presented a high risk that we might experience a temporary non-dry state for our phalanges, tarsals, and metatarsals. Fortunately, my students bravely waded through the water anyway, and sure enough, their feet eventually dried. I was so proud.

So what was our next-to-last stop on this grand ichnologically tainted tour of the Georgia barrier islands? St. Catherines Island, which is just to the north of Sapelo. Would it reveal some secrets to students and educators alike? Would it have some previously unknown traces, awaiting our discovery and description? Would any of our time there also involve close encounters with large reptilian tracemakers? Signs point to yes. Thanks for reading, and look for that next post soon.

See those two big holes just above the shoreline of this freshwater pond? Those are alligator dens, large burrows that benefit them in many ways. And just to prove this point, these two dens have a pair of alligators hanging out at their entrances. Both alligators are only about 1 meter (3.3 feet) long, though, which means they’re way too small to have been the alligators that made these dens. So what’s going on here? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

See those two big holes just above the shoreline of this freshwater pond? Those are alligator dens, large burrows that benefit them in many ways. And just to prove this point, these two dens have a pair of alligators hanging out at their entrances. Both alligators are only about 1 meter (3.3 feet) long, though, which means they’re way too small to have been the alligators that made these dens. So what’s going on here? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)