This past Friday evening (October 14), Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia hosted the official opening of Selections, a visual-art show themed on evolution, especially as it relates to Charles Darwin. Many other art shows or other creative ventures have revolved around evolutionary themes, especially in 2009, which marked the 150th anniversary of On the Origin of Species and the 200th of Darwin’s birth. But two aspects of this display make it distinctive: (1) it was planned more than two years in advance to accompany the traveling exhibit Darwin, on loan at Fernbank from the American Museum of Natural History; and (2) five of the eight participating artists, all local to the Atlanta area, are also scientists.

Other than once again disproving the notion that artists and scientists live in divergent intellectual realms, once lamented by C.P. Snow in 1969 (for a few other examples of how this false dichotomy is becoming less and less defensible, look here, here, here, here, and here), I am pleased to share that my wife Ruth Schowalter and I are two of the artists in this show. Seven drawings and paintings of ours are on display, with three of those collaborative works, in which we freely mixed scientific concepts with our respective artistic expressions.

Here I will focus on just one of those works, a collaborative piece titled Abstractions of a Rising Sea (2011). My reason for taking a closer look at this one exclusively is because of its having been visually inspired by plant and animal traces of the Georgia barrier islands. Also, in keeping with a Darwinian theme, it depicts how changing environments – in this case, rising sea level – can likewise impact the survival of species, thus affecting the types of traces that are formed and preserved in a given place.

Abstractions of a Rising Sea (2011), by Ruth Schowalter and Anthony Martin: watercolor on paper, 66 X 101 cm (26” X 40”), on display at Fernbank Museum of Natural History until January 1, 2012. But this isn’t just abstract art: it’s also a scientific hypothesis. How so? Please read on. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin.)

Abstractions of a Rising Sea (2011), by Ruth Schowalter and Anthony Martin: watercolor on paper, 66 X 101 cm (26” X 40”), on display at Fernbank Museum of Natural History until January 1, 2012. But this isn’t just abstract art: it’s also a scientific hypothesis. How so? Please read on. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin.)

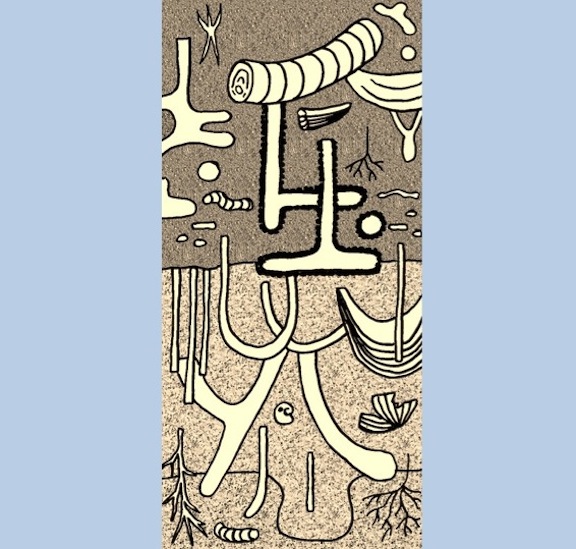

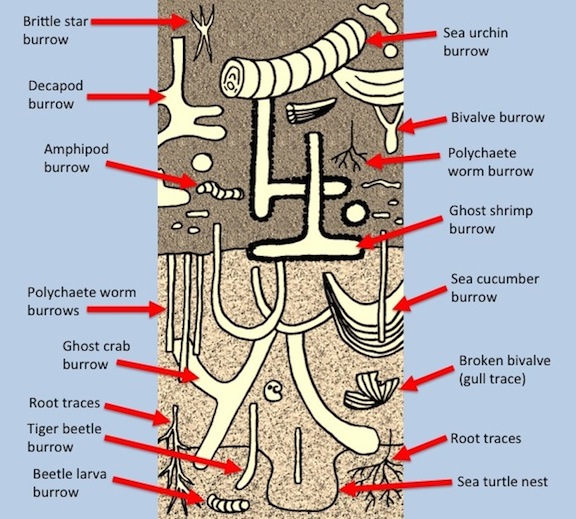

Although this painting may look abstract to most viewers, given its strange, funky shapes and patterns expressed with a colorful palette, its basic elements actually embody an evidence-based prediction. The artwork design, shown below, originated as a conceptual drawing I made for my upcoming book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast; in fact, it will be the last illustration in the book. The drawing, which I later scanned and modified slightly with Adobe Photoshop™, portrays a vertical sequence of traces made by plants and animals on a typical Georgia shoreline, but considerably altered as sea level went up along that shoreline. In short, it reflects my prognosis of how a coastal dune will become inundated by the sea over the next few decades, with traces of marine animals succeeding those of terrestrial plants and animals.

The original illustration that inspired the artwork, which I drew to portray the sequence of traces that would be made in a given place on the Georgia coast as sea level goes up in the next few hundred years. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

The original illustration that inspired the artwork, which I drew to portray the sequence of traces that would be made in a given place on the Georgia coast as sea level goes up in the next few hundred years. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

So if you’ll bear with me for a few minutes, here’s a more detailed explanation. The traces at the bottom of the illustration represent those of a coastal dune, with plant-root traces, insect burrows, and sea-turtle nests. Just above, those traces are replaced by the burrows of ghost crabs, which are semi-terrestrial animals, but dependent on the sea.  A typical Y-shaped burrow of a ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata), viewed in longitudinal section in the eroded face of a coastal dune on Sapelo Island, Georgia. This formerly open burrow was filled from above by sand of a slightly different composition, making it easier to spot. But also note that it cuts across the layering (bedding) of the dune, showing that the crab burrow is relatively younger than the dune deposit. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A typical Y-shaped burrow of a ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata), viewed in longitudinal section in the eroded face of a coastal dune on Sapelo Island, Georgia. This formerly open burrow was filled from above by sand of a slightly different composition, making it easier to spot. But also note that it cuts across the layering (bedding) of the dune, showing that the crab burrow is relatively younger than the dune deposit. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Next are burrows made by marine invertebrates that live in the intertidal and shallow subtidal areas of a beach, such as polychaete worms, sea cucumbers, and acorn worms.

A variety of abandoned polychaete worm burrows, all washed out of their original places by a vigorous waves and tides and found along a beach on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Although each burrow is distinctive, what they share are behavioral adaptations to living in sandy environments dominated by the surf, shown by their reinforced walls. All four species of worms also orient their burrows vertically, which helps prevent too-frequent exhumation. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A variety of abandoned polychaete worm burrows, all washed out of their original places by a vigorous waves and tides and found along a beach on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Although each burrow is distinctive, what they share are behavioral adaptations to living in sandy environments dominated by the surf, shown by their reinforced walls. All four species of worms also orient their burrows vertically, which helps prevent too-frequent exhumation. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Accompanying these is a snail shell (lower third, center) with a drillhole, a cannibalism trace made when a moon snail preyed on its own kind.

Drillhole in the shell of a common moon snail (Neverita duplicata) caused by another moon snail, a trace of both predation and cannibalism: Sapelo Island, Georgia (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Drillhole in the shell of a common moon snail (Neverita duplicata) caused by another moon snail, a trace of both predation and cannibalism: Sapelo Island, Georgia (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A broken clam shell to the right of the snail is a likewise a predation trace, but attributable to a seagull. (The bird flew up with the clam in its beak, dropped it onto a hard-packed beach sand at low tide, and dined on its freshly killed contents.)

Broken shell of the giant Atlantic cockle (Dinocardium robustum), caused by a sea gull that picked it up, flew with it, and dropped it onto a sandflat at low tide on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Broken shell of the giant Atlantic cockle (Dinocardium robustum), caused by a sea gull that picked it up, flew with it, and dropped it onto a sandflat at low tide on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

The upper half of the figure is then dominated by traces of marine invertebrates that live fully submerged offshore, such as ghost shrimp and other crustaceans, other polychaete worms, sea urchins, and brittle stars.

Labeled version of the illustration, depicting an overall progression from onshore traces (bottom) to offshore traces (above). If this sequence of sand and mud were to fossilize, this is how paleontologists and geologists would interpret it. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

Labeled version of the illustration, depicting an overall progression from onshore traces (bottom) to offshore traces (above). If this sequence of sand and mud were to fossilize, this is how paleontologists and geologists would interpret it. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

The preceding artistic-scientific deconstruction should also help a viewer to better understand how geologists think when they look at a vertical sequence of sedimentary rock. For example, geologists follow several basic principles when trying to figure out the relative timing of different events in the geologic past.

One of these is called superposition, in which the effects of the oldest (first occurring) event in a given sequence of sedimentary rock are at the bottom, and the effects of subsequent events are recorded in progressively younger rocks toward the top.

The second principle is cross-cutting relationships, in that whatever is cutting across a previously existing structure must be younger than it. Think about how an animal burrow may cut across burrows made by previous generations of animals, and how you could unravel the sequence of “burrowing events” by simply observing which intersects which burrow.

A third principle is Walther’s Law, named after German geologist Johannes Walther (1960-1937) which states (more-or-less) that laterally adjacent environments succeed one another vertically. In other words, where a maritime forest and coastal dune are next to one another today on the Georgia coast, a drop in sea level means that coastal dunes might by succeeded vertically by the forest. Conversely, sea level going up implies that sediments of offshore environments, which are currently next to the beach and dunes, will some day overlie those of the dune.

Hence the illustration shows all three principles at play with a rising sea. For example, ghost-crab burrows cut across a sea-turtle nest from above, vertical burrows of a polychaete worm in turn dissect ghost-crab burrows below them, and a ghost-shrimp burrow from above interrupts one limb of a U-shaped acorn-worm burrow. Even better, a trained ichnologist can look at this sequence of traces and discern the environmental change that happened over the time represented by the sediments.

You can test this supposition by showing the illustration to other ichnologists, and I predict they will say, “Looks like sea level went up.” As a result, seemingly abstract patterns can become meaningful as we apply these images within the context of time passing, a concept we think Darwin – as a geologist and biologist – would have appreciated.

When I first showed this illustration to Ruth, she was quite taken by its forms and compositions, and she imagined what it would look like made much larger and in color. So we got to work on it, purposefully choosing a large piece of watercolor paper, onto which I drew the ichnological design. She then composed the color scheme, using a combination of water-color pencils and brushes, and I painted in a few details here and there, but most of the hard work was hers.

Ruth and my artistic styles are quite different – she’s a visionary artist, whereas I’m a more of a surrealist – but we both agree that meaningful art should provoke thought. So we very much like how this artwork also addresses and combines two contentious issues in American society: evolutionary theory and global-climate change. In Georgia, as in many other places in the U.S., scientists and science-educators still encounter resistance to the teaching of evolution, despite its extensive testing during the past 150 years and its consequent acceptance by virtually all scientists worldwide. Likewise, in recent years, so-called “global-warming deniers” have put much effort into rebuffing, ignoring, or otherwise downplaying the effects of human-caused climate change – despite near-universal scientific consensus – resulting in the twisting of scientists’ words or outright censorship.

For the plants, animals, and people who live on the Georgia coast, politically charged arguments become pointless as the shoreline moves up and over the land. As global climate continues to change and sea level goes up along the Georgia coast, how will life respond to these changes, especially if the sea rises faster than most organisms can adapt? This is a question we could have put to Charles Darwin, and one we attempt to pose through this synthesis of art and science.

(Acknowledgements to my wife and art-science collaborator, Ruth Schowalter, for her invaluable input on this post: thank you! Selections, featuring the artwork discussed here as well as others by us and six other artists, will be showing at Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia until January 1, 2012. Admission to the museum includes viewing of the artwork, permanent exhibits, and the Darwin exhibit.)

Further Reading

Pilkey, O.H., and Fraser, M.E., 2005. A Celebration of the World’s Barrier Islands. Columbia University Press, New York: 400 p.

Purcell, W.S., and Gould, S.J., 2000. Crossing Over: Where Art and Science Meet. Three Rivers Press, New York: 159 p.

Trusler, P., Vickers-Rich, P., and Rich, T.H., 2010. The Artist and the Scientists: Bringing Prehistory to Life. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.: 320 p.