After visiting Cumberland Island and Jekyll Island, our Barrier Islands class had entered its third day (Monday, March 11), and was now about to embark onto our third and fourth barrier islands of the Georgia coast. These islands were a Pleistocene-Holocene pair – St. Simons and Little St. Simons, respectively – and the latter was our primary goal. After all, Little St. Simons is a privately owned and undeveloped island, one of the few that has not been logged or otherwise majorly altered by those ever-nefarious and industrious post-Enlightenment humans. St Simons, though, had its own lessons to teach us, including a realization I had that ichnological factors (bivalve feces, specifically) had played a role in deciding the fate of European power struggles on the Georgia coast during the 18th century.

Just like the previous two posts, this one will be told through photos and captions, which I hope captures much of what my students and I learned during our times on these two islands. Just watch out for those tails.

Little St. Simons is a privately owned island, but is available for day tours of groups like ours that are led by their knowledgeable and friendly naturalists. Soon after arriving by small boats on the island and being greeted by the naturalists assigned to us, Laura (pictured) and Ben (you’ll see him soon enough). While there, Laura provided a brief introduction to the geological history of Little St. Simons: Holocene (probably only a few thousands years old), and rapidly gaining weight (sediment, that is) each year, supplied by the nearby Altamaha River.

Little St. Simons is a privately owned island, but is available for day tours of groups like ours that are led by their knowledgeable and friendly naturalists. Soon after arriving by small boats on the island and being greeted by the naturalists assigned to us, Laura (pictured) and Ben (you’ll see him soon enough). While there, Laura provided a brief introduction to the geological history of Little St. Simons: Holocene (probably only a few thousands years old), and rapidly gaining weight (sediment, that is) each year, supplied by the nearby Altamaha River.

Check out our air-conditioned field vehicles! Seeing that this is a field course, traveling this way was ideal for experiencing the island a bit more directly, yet without descending in a Heart-of-Darkeness or Lord-of-the-Flies sort of mode. Because that would be bad.

Check out our air-conditioned field vehicles! Seeing that this is a field course, traveling this way was ideal for experiencing the island a bit more directly, yet without descending in a Heart-of-Darkeness or Lord-of-the-Flies sort of mode. Because that would be bad.

Little St. Simons has a healthy number of freshwater wetlands for such a small island (like this one), more closely resembling what used to be on the Georgia barrier islands before a few people decided that plantations and paper mills were great ideas.

Little St. Simons has a healthy number of freshwater wetlands for such a small island (like this one), more closely resembling what used to be on the Georgia barrier islands before a few people decided that plantations and paper mills were great ideas.

Say, isn’t that an all-American bird? Yes, it is, but more importantly, it has a rather prominent trace next to it – a bald eagle nest – that is also occupied by a couple of young eagles. (Here, one is sticking its head out of the nest while being overseen by a protective parent.) Bald eagle nests are among the largest tree nests made by any modern bird, leading me to wonder what tree-dwelling dinosaur nests from the Cretaceous Period must have looked like.

Say, isn’t that an all-American bird? Yes, it is, but more importantly, it has a rather prominent trace next to it – a bald eagle nest – that is also occupied by a couple of young eagles. (Here, one is sticking its head out of the nest while being overseen by a protective parent.) Bald eagle nests are among the largest tree nests made by any modern bird, leading me to wonder what tree-dwelling dinosaur nests from the Cretaceous Period must have looked like.

Sorry folks, can’t get enough of bird traces on this island. Many of the tree trunks on Little St. Simons bear the horizontally aligned holes of yellow-bellied sapsuckers. These woodpeckers pierce tree trunks to cause the tree to bleed sap, which attracts insects, which get stuck, which get eaten by the sapsuckers. Sap + insects = tasty treat!

Sorry folks, can’t get enough of bird traces on this island. Many of the tree trunks on Little St. Simons bear the horizontally aligned holes of yellow-bellied sapsuckers. These woodpeckers pierce tree trunks to cause the tree to bleed sap, which attracts insects, which get stuck, which get eaten by the sapsuckers. Sap + insects = tasty treat!

Armadillo tracks on a coastal dune at the north end of the island show just how far-ranging these mammals can get. Having only recently arrived to the Georgia coast since the 1970s, these prolific tracemakers are now on every island.

Armadillo tracks on a coastal dune at the north end of the island show just how far-ranging these mammals can get. Having only recently arrived to the Georgia coast since the 1970s, these prolific tracemakers are now on every island.

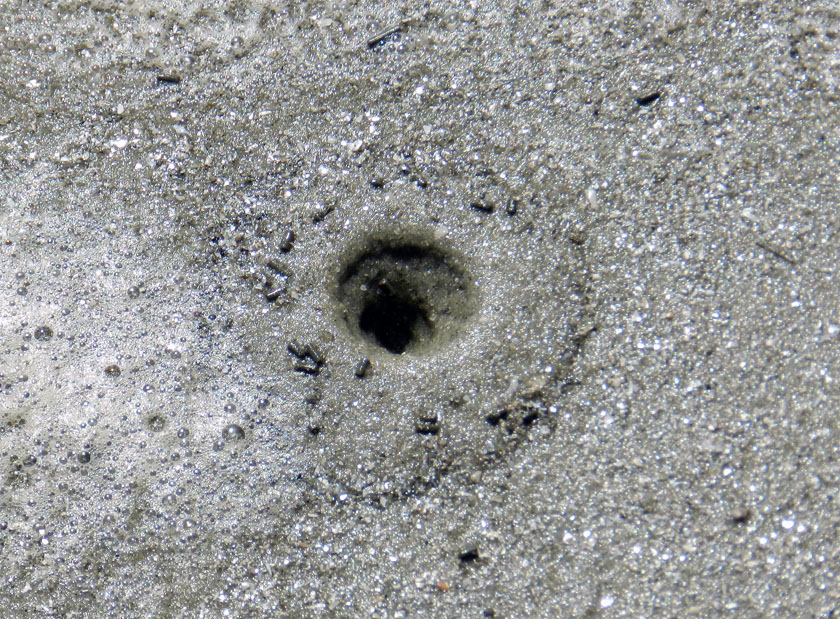

Near the armadillo tracks, also in the coastal dunes, were these mystery burrows. I had no idea what made these, as they were too small to be mole burrows, too big to be insect burrows, and too horizontal to be mouse burrows. Just a reminder that even the author of a 700-page book about Georgia-coast traces still has a lot more to learn.

Near the armadillo tracks, also in the coastal dunes, were these mystery burrows. I had no idea what made these, as they were too small to be mole burrows, too big to be insect burrows, and too horizontal to be mouse burrows. Just a reminder that even the author of a 700-page book about Georgia-coast traces still has a lot more to learn.

Aw, look at this cute little baby alligator, which was near its momma in one of the freshwater ponds on Little St. Simons. I wonder where it came from originally?

Aw, look at this cute little baby alligator, which was near its momma in one of the freshwater ponds on Little St. Simons. I wonder where it came from originally?

Why, there’s where it came from: it’s momma’s nest! The arrow is pointing toward a now mostly collapsed alligator nest, which hatched the little tykes that are now in the nearby wetland. Alligator nests are composed mostly of loose vegetation that the mother collects and piles, enough that it will give off heat to incubate her eggs. Such nests have very poor preservation potential in the fossil record, but it is still very interesting to study how they disintegrate so rapidly.

Why, there’s where it came from: it’s momma’s nest! The arrow is pointing toward a now mostly collapsed alligator nest, which hatched the little tykes that are now in the nearby wetland. Alligator nests are composed mostly of loose vegetation that the mother collects and piles, enough that it will give off heat to incubate her eggs. Such nests have very poor preservation potential in the fossil record, but it is still very interesting to study how they disintegrate so rapidly.

Alligators (left) and birds (right, with one on her nest) last shared a common ancestor early in the Mesozoic Era, but here they are, working together to their mutual benefit. Great egrets and woodstorks nest on islands, which are guarded by large alligators, who are good deterrents to egg predators. (In a grudge match between an alligator and raccoon, who do you think would win?) As payment for this protection, alligators get an occasional chick falling out of the nest, a small evolutionary price for the birds to pay when compared to an entire clutch of eggs getting munched.

Alligators (left) and birds (right, with one on her nest) last shared a common ancestor early in the Mesozoic Era, but here they are, working together to their mutual benefit. Great egrets and woodstorks nest on islands, which are guarded by large alligators, who are good deterrents to egg predators. (In a grudge match between an alligator and raccoon, who do you think would win?) As payment for this protection, alligators get an occasional chick falling out of the nest, a small evolutionary price for the birds to pay when compared to an entire clutch of eggs getting munched.

My, what a noisy tail you have! We were delighted to encounter this diamondback rattlesnake on one of the sandy roads of Little St. Simons, which urged us to approach it carefully, using a clearly audible warning and threat postures. (P.S. It worked.)

My, what a noisy tail you have! We were delighted to encounter this diamondback rattlesnake on one of the sandy roads of Little St. Simons, which urged us to approach it carefully, using a clearly audible warning and threat postures. (P.S. It worked.)

Our other guide, Ben, had an obviously deep affection for venomous reptiles, expressed first through some impromptu snake-handling. (No, he did not use his hands, nor did he speak in tongues. See that snake-handling device in his right hand?) Following our not-too-close encounter, he expounded on the ecological importance of rattlesnakes to the island, and related some interesting facts about rattlesnake behavior. Gee, you think the students might remember some of this lesson? (Personal note: Bring rattlesnakes into the classroom more often.)

Our other guide, Ben, had an obviously deep affection for venomous reptiles, expressed first through some impromptu snake-handling. (No, he did not use his hands, nor did he speak in tongues. See that snake-handling device in his right hand?) Following our not-too-close encounter, he expounded on the ecological importance of rattlesnakes to the island, and related some interesting facts about rattlesnake behavior. Gee, you think the students might remember some of this lesson? (Personal note: Bring rattlesnakes into the classroom more often.)

At the south end of Little St. Simons is a very nice beach, and on that beach were – you guessed it – shorebird tracks. Here are some plover tracks, which could be from Wilson’s plovers, semi-palmated plovers, or some other species.

At the south end of Little St. Simons is a very nice beach, and on that beach were – you guessed it – shorebird tracks. Here are some plover tracks, which could be from Wilson’s plovers, semi-palmated plovers, or some other species.

Sadly enough, our tour of Little St. Simons lasted only until 3:00 p.m., so we had some time on St. Simons to do a bit more learning. So I decided we would stop at Fort Frederica National Monument, on the north end of St. Simons Island. It turned out this was a educationally sound decision, especially when one of the rangers on duty – Mr. Ted Johnson (right) – volunteered to give our group a spirited and informative lecture about the former military importance of Fort Frederica. However, judging from the downcast looks on several of the students, I imagine they were already missing alligators, snakes, and shorebirds of Little St. Simons Island, and (of course) their traces.

Sadly enough, our tour of Little St. Simons lasted only until 3:00 p.m., so we had some time on St. Simons to do a bit more learning. So I decided we would stop at Fort Frederica National Monument, on the north end of St. Simons Island. It turned out this was a educationally sound decision, especially when one of the rangers on duty – Mr. Ted Johnson (right) – volunteered to give our group a spirited and informative lecture about the former military importance of Fort Frederica. However, judging from the downcast looks on several of the students, I imagine they were already missing alligators, snakes, and shorebirds of Little St. Simons Island, and (of course) their traces.

The most obvious human traces at Fort Frederica are these “footprints” (foundations) of some of the buildings there in the 18th century. Established as a British outpost in Georgia to compete with the Spanish presence to the south, Fort Frederica was a thriving town as long as the military was there.

The most obvious human traces at Fort Frederica are these “footprints” (foundations) of some of the buildings there in the 18th century. Established as a British outpost in Georgia to compete with the Spanish presence to the south, Fort Frederica was a thriving town as long as the military was there.

OK, you’ve no doubt read this far to find out how bivalve feces helped the English to defeat the Spanish in the mid-18th century and consequently gain a permanent foothold in Georgia (until those pesky colonials defeated them later that century, that is). See where the fort is located? Right on a point, facing a tidal channel, and with salt marsh on either side of it. Because the salt marshes are largely composed of feces and similar muddy ejecta of ribbed mussels and other invertebrates, these make for wonderfully gooey substrates. Such substrates tend to discourage rapid movement of ordinance-laden ground troops, which forced the Spanish to try other means for attacking the fort, which failed. Bivalve feces for the win! Traces rule! ¡En la cara, los conquistadores!

OK, you’ve no doubt read this far to find out how bivalve feces helped the English to defeat the Spanish in the mid-18th century and consequently gain a permanent foothold in Georgia (until those pesky colonials defeated them later that century, that is). See where the fort is located? Right on a point, facing a tidal channel, and with salt marsh on either side of it. Because the salt marshes are largely composed of feces and similar muddy ejecta of ribbed mussels and other invertebrates, these make for wonderfully gooey substrates. Such substrates tend to discourage rapid movement of ordinance-laden ground troops, which forced the Spanish to try other means for attacking the fort, which failed. Bivalve feces for the win! Traces rule! ¡En la cara, los conquistadores!

As our day neared an end, my students decided that an appropriate way to signal their pleasure with all they had learned was for them to give me the now-official fiddler crab salute, waving their mock claws in unison. We all plan to still use this when greeting on the Emory campus, which should thoroughly mystify other students, faculty, and especially administrators, the latter of whom will wonder if it is some sort of secret-society sign. (Which, in a sense, it will be. Be afraid. Be very afraid)

As our day neared an end, my students decided that an appropriate way to signal their pleasure with all they had learned was for them to give me the now-official fiddler crab salute, waving their mock claws in unison. We all plan to still use this when greeting on the Emory campus, which should thoroughly mystify other students, faculty, and especially administrators, the latter of whom will wonder if it is some sort of secret-society sign. (Which, in a sense, it will be. Be afraid. Be very afraid)

What island was next on our journey? My old favorite, Sapelo Island, just to the north of Little St. Simons and St. Simons, and as different from these as the preceding islands were from one another. Stay tuned for those photos and comments in just a few days, and get ready to learn.