The end of another revolution of the earth around the sun brings with it many “best,” “most,” “worst,” “sexiest,” or other such lists associated with that 365-day cycle. Tragically, though, none of these lists have involved traces or trace fossils. So seeing that the end of 2012 also coincides with the release of my book (Life Traces of the Georgia Coast), I thought that now might be a good time to start the first of what I hope will be an annual series highlighting the most interesting traces I encountered on the Georgia barrier islands during the year.

In 2012, I visited three islands at three separate times: Cumberland Island in February, St. Catherines Island in March, and Jekyll Island in November. As usual, despite having done field work on these islands multiple times, each of these most recent visits in 2012 taught me something new and inspired posts that I shared through this blog.

For the Cumberland Island visit, it was seeing many coquina clams (Donax variabilis) in the beach sands there at low tide, and marveling at their remarkable ability to “listen” to and move with the waves. With St. Catherines Island, it was to start describing and mapping the alligator dens there, using these as models for similar large reptile burrows in the fossil record. Later in the year, I presented the preliminary results of this research at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. For the Jekyll trip, which was primarily for a Thanksgiving-break vacation with my wife Ruth, two types of traces grabbed my attention, deer tracks on a beach and freshwater crayfish burrows in a forested wetland. So despite all of the field work I had done previously on the Georgia coast, these three trips in 2012 were still instrumental in teaching me just a little more I didn’t know about these islands, which deserve to be scrutinized with fresh eyes each time I step foot on them and leave my own marks.

For this review, I picked out three photos of traces from each island that I thought were provocatively educational, imparting what I hope are new lessons to everyone, from casual observers of nature to experienced ichnologists.

Cumberland Island

Coyote tracks – Coyotes (Canis latrans) used to be rare tracemakers on the Georgia barrier islands, but apparently have made it onto nearly all of the islands in just the past ten years or so. On Cumberland, despite its high numbers of visitors, people almost never see these wild canines. This means we have to rely on their tracks, scat, and other sign to discern their presence, where they’re going, and what they’re doing. I saw these coyote tracks while walking with my students along a trail between the coastal dunes, and they made for good in-the-field lessons on “What was this animal?” and “What was it doing?” Because Cumberland is designated as a National Seashore and thus is under the jurisdiction of the U.S. National Park Service, I’m interested in watching how they’ll handle the apparent self-introduction of this “new” predator to island ecosystems, which may begin competing with the bobcats (Lynx rufus) there for the same food resources.

Coyote tracks – Coyotes (Canis latrans) used to be rare tracemakers on the Georgia barrier islands, but apparently have made it onto nearly all of the islands in just the past ten years or so. On Cumberland, despite its high numbers of visitors, people almost never see these wild canines. This means we have to rely on their tracks, scat, and other sign to discern their presence, where they’re going, and what they’re doing. I saw these coyote tracks while walking with my students along a trail between the coastal dunes, and they made for good in-the-field lessons on “What was this animal?” and “What was it doing?” Because Cumberland is designated as a National Seashore and thus is under the jurisdiction of the U.S. National Park Service, I’m interested in watching how they’ll handle the apparent self-introduction of this “new” predator to island ecosystems, which may begin competing with the bobcats (Lynx rufus) there for the same food resources.

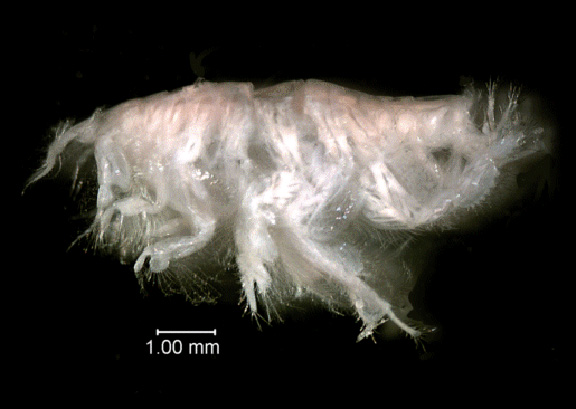

Ghost Shrimp Burrows, Pellets and Buried Whelk – Sometimes the traces on the beaches at low tide are subtle in what they tell us, and the traces in this photo qualify as ones that could be easily overlooked. The three little holes in the photo are the tops of ghost shrimp burrows. Scattered about on the beach surface are fecal pellets made by the same animals; ghost shrimp are responsible for most of the mud deposition on the sandy beaches of Georgia. The triangular “trap door” in the middle of the photo is from a knobbed whelk (Busycon carica), which has buried itself directly under the sand surface. The ghost shrimp are perhaps as deep as 1-2 meters (3.3-6.6 ft) below the surface, and are feeding on organics in their subterranean homes. These homes are complex, branching burrow systems, reinforced by pelleted walls. Hence these animals and their traces provide a study in contrasts of adaptations, tiering, and fossilization potential. The whelk trace is ephemeral, and could be wiped out with the next high tide, especially if the waiting whelk emerges and its shallow burrow collapses behind it. On the other hand, only the top parts of the ghost shrimp burrows are susceptible to erosion, meaning their lower parts are much more likely to win in the fossilization sweepstakes.

Ghost Shrimp Burrows, Pellets and Buried Whelk – Sometimes the traces on the beaches at low tide are subtle in what they tell us, and the traces in this photo qualify as ones that could be easily overlooked. The three little holes in the photo are the tops of ghost shrimp burrows. Scattered about on the beach surface are fecal pellets made by the same animals; ghost shrimp are responsible for most of the mud deposition on the sandy beaches of Georgia. The triangular “trap door” in the middle of the photo is from a knobbed whelk (Busycon carica), which has buried itself directly under the sand surface. The ghost shrimp are perhaps as deep as 1-2 meters (3.3-6.6 ft) below the surface, and are feeding on organics in their subterranean homes. These homes are complex, branching burrow systems, reinforced by pelleted walls. Hence these animals and their traces provide a study in contrasts of adaptations, tiering, and fossilization potential. The whelk trace is ephemeral, and could be wiped out with the next high tide, especially if the waiting whelk emerges and its shallow burrow collapses behind it. On the other hand, only the top parts of the ghost shrimp burrows are susceptible to erosion, meaning their lower parts are much more likely to win in the fossilization sweepstakes.

Feral Horse Grazing and Trampling Traces – Probably the most controversial subject related to any so-called “wild” Georgia barrier islands is the feral horses of Cumberland Island, and what to do about their impacts on island ecosystems there. A year ago, I wrote a post about these tracemakers as invasive species, and discussed this same topic with students before we visited in February. But nothing said “impact” better to these students than this view of a salt marsh, overgrazed and trampled along its edges by horses. This is a example of how the cumulative effects of traces made by a single invasive species can dramatically alter an ecosystem, rendering it a less complete version of its original self.

Feral Horse Grazing and Trampling Traces – Probably the most controversial subject related to any so-called “wild” Georgia barrier islands is the feral horses of Cumberland Island, and what to do about their impacts on island ecosystems there. A year ago, I wrote a post about these tracemakers as invasive species, and discussed this same topic with students before we visited in February. But nothing said “impact” better to these students than this view of a salt marsh, overgrazed and trampled along its edges by horses. This is a example of how the cumulative effects of traces made by a single invasive species can dramatically alter an ecosystem, rendering it a less complete version of its original self.

St. Catherines Island

Suspended Bird Nest – I don’t know what species of bird made this exquisitely woven and suspended little nest, but I imagine it is was a wren, and one related to the long-billed marsh wren (Telmatodytes palustris), which also makes suspended nests in the salt marshes. This nest was next to one of several artificial ponds with islands constructed on St. Catherines with the intent of helping larger birds, such as egrets, herons, and wood storks, so that they can use the islands as rookeries. These ponds are also inhabited by alligators, which had left plenty of tracks, tail dragmarks, and other sign along the banks. With virtually no chance of being preserved in the fossil record, this nest was a humbling reminder of what we still don’t know from ichnology, such as when this specialized type of nest building evolved, or whether this behavior happened first in arboreal non-avian dinosaurs or birds.

Suspended Bird Nest – I don’t know what species of bird made this exquisitely woven and suspended little nest, but I imagine it is was a wren, and one related to the long-billed marsh wren (Telmatodytes palustris), which also makes suspended nests in the salt marshes. This nest was next to one of several artificial ponds with islands constructed on St. Catherines with the intent of helping larger birds, such as egrets, herons, and wood storks, so that they can use the islands as rookeries. These ponds are also inhabited by alligators, which had left plenty of tracks, tail dragmarks, and other sign along the banks. With virtually no chance of being preserved in the fossil record, this nest was a humbling reminder of what we still don’t know from ichnology, such as when this specialized type of nest building evolved, or whether this behavior happened first in arboreal non-avian dinosaurs or birds.

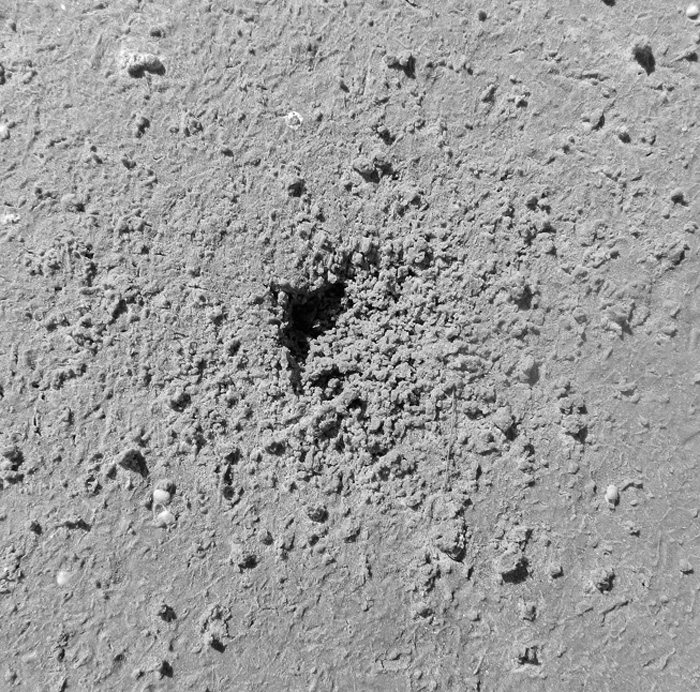

Ant Nest in Storm-Washover Deposit – As you can see, the aperture of this ant nest, as well as the small pile of sand outside of it, did not exactly scream out for attention and demand that its picture be taken. But its location was significant, in that it was on a freshly made storm-washover deposit next to the beach. This “starter nest” gives a glimpse of how ants and other terrestrial insects can quickly colonize sediments dumped by marine processes, such as storm waves. These sometimes-thick storm deposits can cause locally elevated areas above what used to be muddy salt marshes. This means insects and other animals that normally would never burrow into or traverse these marshes move into the neighborhood and set up shop, blissfully unaware that the sediments of a recently buried marginal-marine environment are below them. Ant nests also have the potential to reach deep down to those marine sediments, causing a disjunctive mixing of the traces of marine and terrestrial animals that would surely confuse most geologists looking at similar deposits in the geologic record.

Ant Nest in Storm-Washover Deposit – As you can see, the aperture of this ant nest, as well as the small pile of sand outside of it, did not exactly scream out for attention and demand that its picture be taken. But its location was significant, in that it was on a freshly made storm-washover deposit next to the beach. This “starter nest” gives a glimpse of how ants and other terrestrial insects can quickly colonize sediments dumped by marine processes, such as storm waves. These sometimes-thick storm deposits can cause locally elevated areas above what used to be muddy salt marshes. This means insects and other animals that normally would never burrow into or traverse these marshes move into the neighborhood and set up shop, blissfully unaware that the sediments of a recently buried marginal-marine environment are below them. Ant nests also have the potential to reach deep down to those marine sediments, causing a disjunctive mixing of the traces of marine and terrestrial animals that would surely confuse most geologists looking at similar deposits in the geologic record.

Alligator Tracks in a Salt Marsh – These alligator tracks, which are of the left-side front and rear feet, along with a tail dragmark (right) surprised me for several reasons. One was their size: the rear foot (pes) was about 20 cm (8 in) long, one of the largest I’ve seen on any of the islands. (As my Australian friends might say, it was bloody huge, mate.) This trackway also was unusual because it was on a salt pan, a sandy part of a marsh that lacks vegetation because of its high concentration of salt in its sediments. (According to conventional wisdom, alligators prefer fresh-water environments, not salt marshes.) Yet another oddity was the preservation of scale impressions in the footprints, which I normally only see in firm mud. Finally, the trackway was crosscut by trails of grazing snails and burrows of sand-fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator). This helped me to age the tracks – probably less than 24 hours old, and not so fresh that I should have reason to get worried. (Although I did pay closer attention to my surroundings after finding them.) Overall, this also made for a neat assemblage of vertebrate and invertebrate traces, one I would be delighted to find in the fossil record from the Mesozoic Era.

Alligator Tracks in a Salt Marsh – These alligator tracks, which are of the left-side front and rear feet, along with a tail dragmark (right) surprised me for several reasons. One was their size: the rear foot (pes) was about 20 cm (8 in) long, one of the largest I’ve seen on any of the islands. (As my Australian friends might say, it was bloody huge, mate.) This trackway also was unusual because it was on a salt pan, a sandy part of a marsh that lacks vegetation because of its high concentration of salt in its sediments. (According to conventional wisdom, alligators prefer fresh-water environments, not salt marshes.) Yet another oddity was the preservation of scale impressions in the footprints, which I normally only see in firm mud. Finally, the trackway was crosscut by trails of grazing snails and burrows of sand-fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator). This helped me to age the tracks – probably less than 24 hours old, and not so fresh that I should have reason to get worried. (Although I did pay closer attention to my surroundings after finding them.) Overall, this also made for a neat assemblage of vertebrate and invertebrate traces, one I would be delighted to find in the fossil record from the Mesozoic Era.

Jekyll Island

Grackle Tracks and Obstacle Avoidance – These tracks from a boat-tailed grackle (Quiscalus major), spotted just after sunrise on a coastal dune of Jekyll Island, are beautifully expressed, but also tell a little story, and one we might not understand unless we put ourselves down on its level. Why did it jog slightly to the right and then meander to the left, before curving off to the right again? I suspect it was because the small strands of bitter panic grass (Panicum amarum), sticking up out of the dune sand, got in its way. Similar to how we might avoid small saplings while walking through an otherwise open area, this grackle chose the path of least resistance, which involved walking around these obstacles, rather than following a straight line. If we didn’t know about this from such modern examples, but we found a fossil bird trackway like this but didn’t look for nearby root traces, how else might we interpret it?

Grackle Tracks and Obstacle Avoidance – These tracks from a boat-tailed grackle (Quiscalus major), spotted just after sunrise on a coastal dune of Jekyll Island, are beautifully expressed, but also tell a little story, and one we might not understand unless we put ourselves down on its level. Why did it jog slightly to the right and then meander to the left, before curving off to the right again? I suspect it was because the small strands of bitter panic grass (Panicum amarum), sticking up out of the dune sand, got in its way. Similar to how we might avoid small saplings while walking through an otherwise open area, this grackle chose the path of least resistance, which involved walking around these obstacles, rather than following a straight line. If we didn’t know about this from such modern examples, but we found a fossil bird trackway like this but didn’t look for nearby root traces, how else might we interpret it?

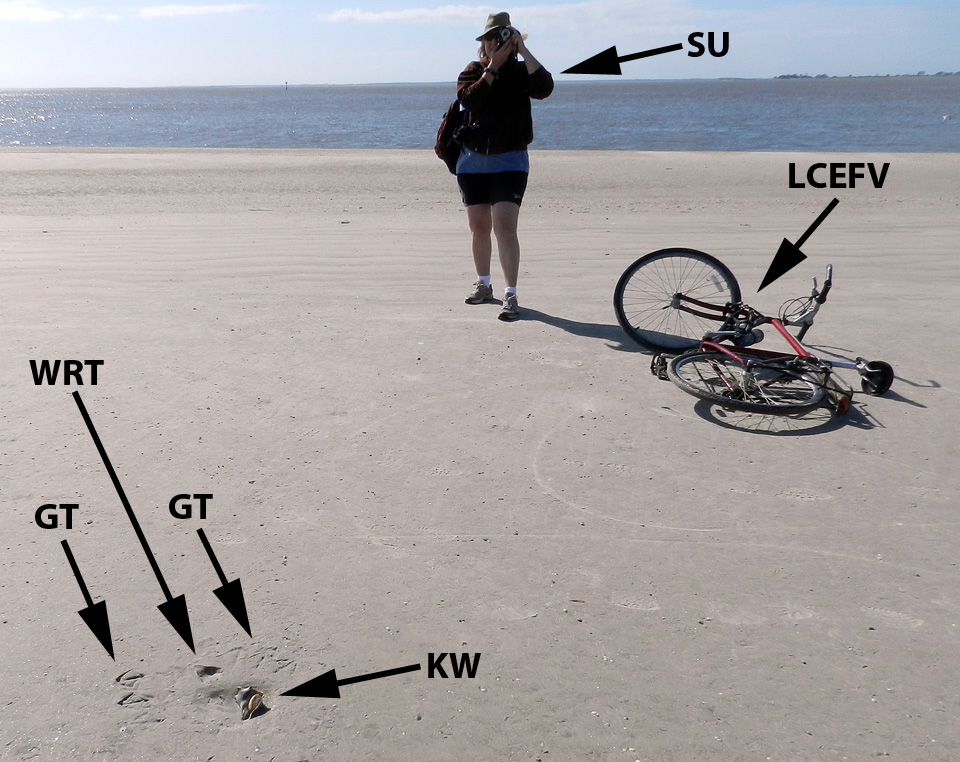

Acorn Worm Burrow, Funnels and Pile – When I came across the top of this acorn-worm burrow, which was probably from the golden acorn worm (Balanoglossus aurantiactus), and on a beach at the north end of Jekyll, I realized I was looking at a two-dimensional expression of a three-dimensional structure. Acorn worms make deep and wide U-shaped vertical burrows, in which they quite sensibly place their mouth at one end and their anus at the other. These burrows usually have a small funnel at the top of one arm of the “U,” which is the “mouth end.” The “anus end” is denoted by a pile of what looks like soft-serve ice cream, which it most assuredly is not, as this is its fecal casting, squirted out of the burrow. What was interesting about this burrow is the nearby presence of a second funnel. This signifies that the worm shifted its mouth end laterally by adding a new burrow shaft to the previous one, superimposing a little “Y” to that part of the U-shaped burrow.

Acorn Worm Burrow, Funnels and Pile – When I came across the top of this acorn-worm burrow, which was probably from the golden acorn worm (Balanoglossus aurantiactus), and on a beach at the north end of Jekyll, I realized I was looking at a two-dimensional expression of a three-dimensional structure. Acorn worms make deep and wide U-shaped vertical burrows, in which they quite sensibly place their mouth at one end and their anus at the other. These burrows usually have a small funnel at the top of one arm of the “U,” which is the “mouth end.” The “anus end” is denoted by a pile of what looks like soft-serve ice cream, which it most assuredly is not, as this is its fecal casting, squirted out of the burrow. What was interesting about this burrow is the nearby presence of a second funnel. This signifies that the worm shifted its mouth end laterally by adding a new burrow shaft to the previous one, superimposing a little “Y” to that part of the U-shaped burrow.

Ghost Crab Dragging Its Claw – As ubiquitous and prolific tracemakers in coastal dunes of the Georgia barrier islands, and as many times as I have studied their traces, I can always depend on ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata) to leave me signs telling of some nuanced variations in their behavior. In this instance, I saw the finely sculpted, parallel, wavy grooves toward the upper middle of its trackway, made while the crab walked sideways from left to right. A count of the leg impressions in the trackway yielded “eight,” which is the number of its walking legs. This means the fine grooves could only come from some appendage other than its walking legs: namely, one of its claws. Why was it dragging its claw? I like to think that it might have been doing something really cool, like acoustical signaling, but it also might have just been a little tired, having spent too much time outside of its burrow.

Ghost Crab Dragging Its Claw – As ubiquitous and prolific tracemakers in coastal dunes of the Georgia barrier islands, and as many times as I have studied their traces, I can always depend on ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata) to leave me signs telling of some nuanced variations in their behavior. In this instance, I saw the finely sculpted, parallel, wavy grooves toward the upper middle of its trackway, made while the crab walked sideways from left to right. A count of the leg impressions in the trackway yielded “eight,” which is the number of its walking legs. This means the fine grooves could only come from some appendage other than its walking legs: namely, one of its claws. Why was it dragging its claw? I like to think that it might have been doing something really cool, like acoustical signaling, but it also might have just been a little tired, having spent too much time outside of its burrow.

So now you know a little more about who left their marks on the Georgia barrier islands in 2012. What will 2013 bring? Let’s find out, with open eyes and minds.