All scientists use tools when investigating how the natural world works. Yet as a traditionally trained field scientist – and an ichnologist – I’ve always been wary of adopting anything more complicated than field notebooks, pencils, tape measures, hand lenses, and cameras. Granted, I did add GPS units to my equipment list starting about 12 years ago and now consider these location-finding devices as standard (and essential) field gear. Still, if you told me even a year ago that I would happily welcome the services of flying robots while tracking alligators on the Georgia barrier islands, I would have smiled and said, “Yes, and Bud Light is my favorite beer.” (Just to clarify: It is not, nor will it ever be.)

Need a better overhead view of barrier-island ecosystems with identified locations, and don’t feel like waiting for the latest satellite photos? I suggest strapping a camera and GPS unit onto a vulture and training it to take pictures while simultaneously recording waypoints. Or, have an aerial drone do the same for you, which will do a much better job, while also not annoying the vulture. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Need a better overhead view of barrier-island ecosystems with identified locations, and don’t feel like waiting for the latest satellite photos? I suggest strapping a camera and GPS unit onto a vulture and training it to take pictures while simultaneously recording waypoints. Or, have an aerial drone do the same for you, which will do a much better job, while also not annoying the vulture. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

So here I am, ready to buy everyone a round of their favorite beverage (perhaps Kool-Aid) in celebration of my being wrong. Earlier this year, an Emory colleague of mine – Michael Page – convinced me that an aerial drone might be a good tool for getting overhead views of ecosystems on the Georgia barrier islands. So as soon as Emory purchased a new, state-of-the-art drone in early 2015, Michael and I plotted to take it to St. Catherines Island for its first real field test in March 2015.

Yeah, I know, it’s not New Horizons, but this drone is still a pretty nifty piece of field equipment, and I’m glad to have added it to my ichnology utility belt. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Yeah, I know, it’s not New Horizons, but this drone is still a pretty nifty piece of field equipment, and I’m glad to have added it to my ichnology utility belt. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

The last time Michael and I were on St. Catherines Island together was two years ago, when we had a group of Emory students help us map gopher tortoise burrows and alligator dens there. (That was fun.) We’ve also been working with a few other colleagues at Georgia Southern University to describe the gopher tortoise burrows and alligator dens on St. Catherines Island over the past few years. So Michael and I figured we could use the drone to aid in this research, starting with the gopher-tortoise burrows.

Perhaps the most persuasive point Michael made about the drone’s potential value was its winning combination of built-in GPS and high-definition video camera. This meant we could instantly map (“georeference”) gopher-tortoise trails between their burrows, as well as the burrows themselves. The latter were easily visible from the wide, white, sandy aprons just outside burrows entrances, and sometimes even show up in satellite photos of the area. The big difference with using a drone versus satellite photos, though, would be in their ‘real-time” capture of these traces – rather than a randomly taken satellite image – while also having much better resolution.

See that hole in the ground? That’s a gopher-tortoise burrow. See those breaks in the grass to the left and right in the foreground, and elsewhere? Those might be trails that connect this burrow to others in the area. How to map all of them? Call in the drone! (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

See that hole in the ground? That’s a gopher-tortoise burrow. See those breaks in the grass to the left and right in the foreground, and elsewhere? Those might be trails that connect this burrow to others in the area. How to map all of them? Call in the drone! (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

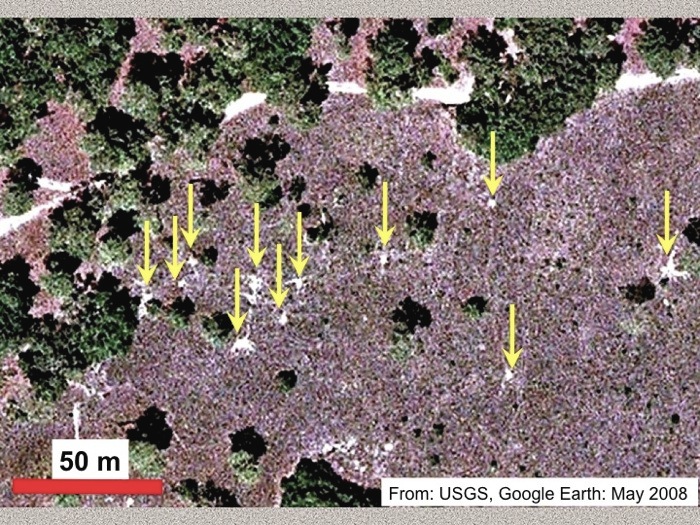

Can you see gopher tortoise traces from space? Surprisingly, yes. Not only are burrow aprons visible in this GoogleEarth™ photo (denoted by the arrows), but also trails connecting some of the burrows. Although if you find yourself squinting and turning your head sideways to see these, you’ll understand why sending up a drone with a high-resolution camera might be a better way to map these traces. (Image taken from a presentation I gave at the 2011 annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

Can you see gopher tortoise traces from space? Surprisingly, yes. Not only are burrow aprons visible in this GoogleEarth™ photo (denoted by the arrows), but also trails connecting some of the burrows. Although if you find yourself squinting and turning your head sideways to see these, you’ll understand why sending up a drone with a high-resolution camera might be a better way to map these traces. (Image taken from a presentation I gave at the 2011 annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

Most of the gopher-tortoise burrows are in a broad, flat area on St. Catherines that used to be pasture land, but is now being restored to the tortoises’ long-leaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem. This re-located tortoise population has done quite well here, and because of its isolation on St. Catherines, it’s an example of one that does not face as many human-related problems as their compatriots on the Georgia mainland. Its remote location also helped us with trying out the drone, as we didn’t have to worry about it dodging buildings, power lines, or gawking locals, all of which might have complicated its flights.

Almost ready for take-off! Drone pilots/wranglers Alison Hight (left) and Michael Page (right) look for a flat place near a staked gopher-tortoise burrow for setting down our “eyes in the sky.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Almost ready for take-off! Drone pilots/wranglers Alison Hight (left) and Michael Page (right) look for a flat place near a staked gopher-tortoise burrow for setting down our “eyes in the sky.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

This was the drone’s maiden voyage on St. Catherines Island, taking off from the gopher-tortoise field. It did just fine. (Video footage by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

The drone pilots doing a great job, sending the drone around the gopher-tortoise field for a spin. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

The drone pilots doing a great job, sending the drone around the gopher-tortoise field for a spin. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

This flight was a big success, in that the drone went up, took lots of video and photos while in the air – all of which was georeferenced – and it came down without crashing. So we decided to try it elsewhere. That’s when we remembered the Atlantic Ocean was only about 500 meters away on the eastern edge of St. Catherines, with a lengthy beach, salt marshes, storm-washover fans, tidal creeks, and a bluff of Pleistocene sand with maritime forest on top of it. So off we went, and we did Flight #2 over the storm-washover fans, salt marshes, and tidal creeks near the north end of the island.

Drones (much like me) operate well in places with wide-open spaces that involve Georgia beaches. Check out how quickly it disappears from view once in the air. (Video footage by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Following this flight, we decided to send the drone father north to survey the bluff from just offshore. This was probably the most exciting flight, as we watched it go out to sea, then fly parallel to the shore, with its camera trained on the coastline.

Michael setting down the drone on a almost-flat surface as Alison prepares it for take-off. The yellow yardstick serves as an easily visible scale that can be used to estimate ground-level distances. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Michael setting down the drone on a almost-flat surface as Alison prepares it for take-off. The yellow yardstick serves as an easily visible scale that can be used to estimate ground-level distances. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Off we go, into the wild blue yonder. (Video footage by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Bringing it back home. Look for the spot near the top-center of the photo for our “hand lens in the sky.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Bringing it back home. Look for the spot near the top-center of the photo for our “hand lens in the sky.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Coming in for a soft landing, which is much preferred over the other type of landing. (Video footage by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

So following these inland and coastal successes, which clearly were applicable to studying gopher tortoises and coastal geology, it was time to try using the drone to look at the apex predators of the island – alligators – and their traces. The next day,while scouting areas further to the south for alligator dens and tracks, we paused on a causeway cutting through a salt marsh. Because the marsh was at low tide, its mudflats were exposed, which allowed a few big animals to walk across it and leave their tracks, and for us to see these tracks.

At least two of the trackways were from alligators, made distinctive by their sinuous tail drags, arcing footprints, and belly drags. I suspect the other trackways were from feral hogs, but I couldn’t tell for sure because they were in squishy mud beyond my carrying capacity. Which is to say, I would have quickly immersed myself in this environment had I gone any further out. Gee, if only we had some way to photograph those trackways from above, better helping us to see their lengths, patterns, and directions.

A salt-marsh mudflat at low tide, with low marsh and a patch of forest (hammock) in the background. See the alligator trackway to the left, where the alligator turned? Look in the middle and you’ll see two more trackways that are probably from feral hogs, and another curving trackway to the right that is from another alligator. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

A salt-marsh mudflat at low tide, with low marsh and a patch of forest (hammock) in the background. See the alligator trackway to the left, where the alligator turned? Look in the middle and you’ll see two more trackways that are probably from feral hogs, and another curving trackway to the right that is from another alligator. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Why wade into waist-deep salt-marsh mud to track an alligator when you can stay safely (and cleanly) on dry land, telling a drone what to do? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Why wade into waist-deep salt-marsh mud to track an alligator when you can stay safely (and cleanly) on dry land, telling a drone what to do? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

So it was time for another flight, and the drone’s first alligator-track-mapping mission, which I’m pleased to say was a success. One example of that success is conveyed by the following photo, which made me gasp when I first saw it. There were the two alligator trackways and the two hog trackways, but also two not-so-clear trackways I had missed and a clear view of where the hogs had dug along the marsh edge. This photo similarly evoked a collective “Ooooo!” when I showed it to an audience the next week at the Southeastern Section meeting of the Geological Society of America meeting in Chattanooga, Tennessee. My talk was a progress report on the alligator dens of St. Catherines Island, but I threw in this photo toward the end of it to show how drones might help with some of our tracking alligator movements through difficult-to-access environments on the island.

OK, you’re probably wondering by now how good those photos and videos taken by the drone might be, and whether or not any useful science can come from them. See that guy in the lower center of the photo? That’s me, pointing to each of the two alligator trackways, with the yellow yardstick providing an additional scale to the left. Notice also the probable feral hog trackways in the middle and fainter ones to the right, as well as the “hogturbation” (rooting disturbance caused by hogs) in the upper left of the photo. As an ichnologist, I was pretty darned pleased by this picture, and I want more like it. (Photograph by The Aerial Drone, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

OK, you’re probably wondering by now how good those photos and videos taken by the drone might be, and whether or not any useful science can come from them. See that guy in the lower center of the photo? That’s me, pointing to each of the two alligator trackways, with the yellow yardstick providing an additional scale to the left. Notice also the probable feral hog trackways in the middle and fainter ones to the right, as well as the “hogturbation” (rooting disturbance caused by hogs) in the upper left of the photo. As an ichnologist, I was pretty darned pleased by this picture, and I want more like it. (Photograph by The Aerial Drone, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Lastly, I was also happy to see that drones have their own ichnology, in that they make flight traces. I’ve been long fascinated by flight traces – called volichnia by ichnologists – and have done my best to describe these in modern birds of the Georgia coast, as well as bird flight traces in the fossil record. Given the right substrate, anatomy, and behavior, the take-off and landing traces of birds and other flighted animals can preserve well enough for us to interpret them for their true nature.

Now, to do the same for a drone requires knowing how they have vertical take-offs and landings, using rapidly moving rotors. This means air will be pushed down onto the substrate directly underneath the drone, then dissipated abruptly outside that zone. The result would be a sem-circular depression slightly more that the maximum width of the drone, and one that would look very much the same whether made by a take-off or landing. The difference would be in the timing of the landing-pad traces: if obscured by the depression, then it was taking off, but if they are impressed on the depression, then it was landing.

Drone coming in for a landing, already pushing aside pine needles on the forest floor and making its landing trace. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Drone coming in for a landing, already pushing aside pine needles on the forest floor and making its landing trace. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

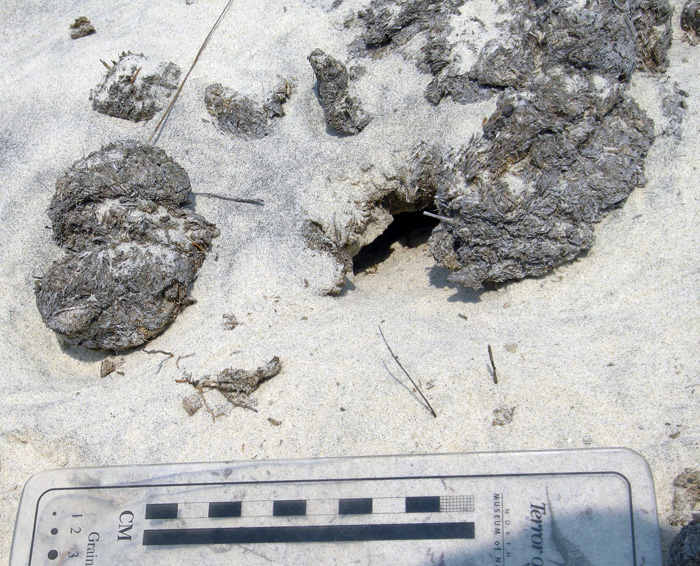

Drone landing trace, minus the drone. Do you see the square pattern in the middle of the oval depression? That’s the outline of the drone, defined by its landing gear. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Drone landing trace, minus the drone. Do you see the square pattern in the middle of the oval depression? That’s the outline of the drone, defined by its landing gear. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

So now we know that a drone can be used for conservation biology, coastal geology, behavioral ecology, and – most importantly – ichnology. How about art? Yes indeed. Once we got back to the Emory campus, Michael handed over the footage to Steve Bransford, a skilled videographer employed by Emory and founder of Terminus Films. Given all of the drone footage, he snipped out the boring parts (always a good thing to do), added a few maps at the start to orient the viewers, put in a soothing soundtrack, and basically created an aesthetically pleasing and extraordinarily educational video. So we submitted it for consideration as an video in the peer-reviewed online journal Southern Spaces, which was founded at Emory University. Much like an aerial drone on an unobstructed coastline, it sailed through peer review and is now available for viewing by all who have an Internet connection.

St. Catherines Island Flyover from Southern Spaces on Vimeo. Never mind the stern message: just click on the link or the video and it will play. Once it does start playing, please watch it on a big screen, sit back, and enjoy the ride. Also be sure to read the accompanying article linked to the peer-reviewed online journal Southern Spaces.

What’s aerial adventures await us next? We’ll see, as we have plenty of visual information and data to process from our previous visit. But for now we can be pleased to have shown the value of an aerial drone as both a scientific instrument and a means for engaging our senses with soaring imaginations.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the St. Catherines Island Foundation for its support of our research on St. Catherines, and to Royce Hayes and Michael Halstead for their assistance on field logistics. We also appreciate the expert piloting of the drone by Alison Hight while on St. Catherines. Steve Bransford did a fantastic job with creating the video for the Southern Spaces article, which should win the Georgia equivalent of an Oscar. Input from the editor of Southern Spaces, Allen Tullos, improved our article accompanying the video, and we are grateful to the staff of Southern Spaces for their quality service in putting this video and article online. And as always, many thanks to Ruth Schowalter for her help and support, in and out of the field.

Emory News (July 15, 2015): Drone Offers Stunning Aerial Views of Georgia’s St. Catherines Island.