Let’s try a science-education experiment. Give a child a live clam and ask, “Can this animal fly?” and I predict her or his answer – accompanied by much giggling – will be “No!’ But if you ask, “Can you fly?”, the answer may change, especially if this child has already flown on an aircraft. So of course humans can fly, but to do this, they require machines, paragliders, or other technological aids in order to move through the air and – this is important – arrive on the ground safely.

For clams that try to fly, they end up with more than shattered dreams. How did these clams (Mercenaria mercenaria, also known as quahogs or “hard clams”) end up doing Humpty-Dumpty impressions on a wooden pier? Please read on. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

For clams that try to fly, they end up with more than shattered dreams. How did these clams (Mercenaria mercenaria, also known as quahogs or “hard clams”) end up doing Humpty-Dumpty impressions on a wooden pier? Please read on. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

In a similar way, clams can fly. They just need a little help from other animals that can fly and willingly give them a temporary lift from the earth they and their molluscan relatives have known for all of their evolutionary history. Compared to most of our forays into the air, though, these flights are much more limited. Clam aerial exploits are brief and mostly vertical, with little time for them to appreciate the view from above or otherwise experience unusual sensations. They go up, then they come down, and fast.

Clams do not have landing gear. So they can hit the ground hard, especially if their free fall happened after a lengthy trip up into the air and the ground surface is hard: think of a sandflat at low tide, a paved parking lot, or a wooden boardwalk. A a result, the most common end to clam flights is a shattered shell, which is quickly followed by the demise of the clam as it is consumed by the very same animal that bestowed it with flight, however brief and self-serving.

Traces of a unidirectional vertically oriented clam flight (otherwise known as “falling”) that did not end well for the clam, but worked perfectly for the flying animal that took it for a ride. Notice the impact trace on the hard sandflat, outlining the ribbed shell of the clam (probably Dinocardium robustum) and bits of shell. Most of the probably-still-alive-but-definitely-dying animal was dragged off to a nearby spot so that its soft parts could be eaten by the same perpetrator that took it for a ride. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Traces of a unidirectional vertically oriented clam flight (otherwise known as “falling”) that did not end well for the clam, but worked perfectly for the flying animal that took it for a ride. Notice the impact trace on the hard sandflat, outlining the ribbed shell of the clam (probably Dinocardium robustum) and bits of shell. Most of the probably-still-alive-but-definitely-dying animal was dragged off to a nearby spot so that its soft parts could be eaten by the same perpetrator that took it for a ride. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

So just what flying animals do such dastardly deeds, taking hapless clams up for a ride, only to drop them to a certain death? By now the gentle reader has probably figured out birds are responsible for this blatant bivalvicide, and some may have already known that seagulls are the most likely culprits. In some coastal areas and during low tides, some seagulls fly over exposed sandflats and mudflats, searching for the outlines of clams buried below the surface. These avian ichnologists then swoop down, land, pick up the clam with their beaks, take off, and then once high enough, they drop them, serving up instant raw clam on the half (or quarter, or eighth) shell. Typically all that is left is a jigsaw puzzle of clamshell pieces and the seagull perpetrator’s footprints, but with the latter only evident on muddy or sandy surfaces amenable to preserving tracks.

Ichnological evidence of who killed the clam, provided by the tracks a laughing gull (Larus altricilla).The other half of the shell was broken by its falling onto the sandflat elsewhere, then the gull carried its clam on the half-shell to a more scenic place for its meal. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

Ichnological evidence of who killed the clam, provided by the tracks a laughing gull (Larus altricilla).The other half of the shell was broken by its falling onto the sandflat elsewhere, then the gull carried its clam on the half-shell to a more scenic place for its meal. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

I found this behavior so compelling that I started my book Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013) with a story about a laughing gull (Larus altricilla) and the traces of its unwitnessed predation on an Atlantic cockle (Dinocardium robustum), seagull behavior on the Georgia coast. I was not the first person to note this method of clam-smashing by seagulls, as it has been documented by other scientists in parts of the U.S. and abroad, and has been caught on video. Amazingly, though, despite more than 15 years of visiting the Georgia coast, I had never actually witnessed seagulls dropping clams. instead I had only performed post-mortem forensics, in which I would find broken clamshells on hard sandflats accompanied by seagull tracks, telling tales of murder most fowl.

Video footage of a western gull (Larus occidentalis) picking up a clam, flying up about 10 meters (> 30 feet), and dropping it onto rocks to crack it open. After this doesn’t work the first time – and after shooing away a potential clam-stealing rival – it tries again, and is presumably successful. It’s almost as if this gull is using a scientific methodology, isn’t it? (The videographer is only credited as ‘Trisera’ on the YouTube page, and I don’t know where it was filmed, but suppose it’s on the western coast of the U.S.)

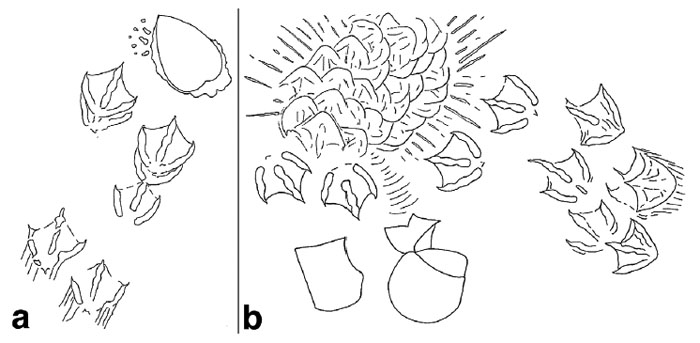

Here’s the first illustration a reader will see in my book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013, Indiana University Press), which I drew to provide a visual forensic analysis of how an Atlantic cockle met its demise at the hands of – er, I mean, wings and bill of – a laughing gull. Part (a) depicts the gull landing after recognizing the outline of the cockle from the air, stopping, and extracting it from the sandflat. Part (b) shows where the cockle was dropped and broken successfully, accompanied by the gull landing and trampling the area as it enjoyed its clam dinner.

Here’s the first illustration a reader will see in my book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013, Indiana University Press), which I drew to provide a visual forensic analysis of how an Atlantic cockle met its demise at the hands of – er, I mean, wings and bill of – a laughing gull. Part (a) depicts the gull landing after recognizing the outline of the cockle from the air, stopping, and extracting it from the sandflat. Part (b) shows where the cockle was dropped and broken successfully, accompanied by the gull landing and trampling the area as it enjoyed its clam dinner.

This meant I was more than overdue to get visual confirmation of gulls killing clams, which was finally granted just a few weeks ago during a recent trip to Jekyll Island (Georgia). It was the day after I had given an invited talk at the annual meeting of The Initiative to Protect Jekyll Island environmental group, and while my wife Ruth and I were relaxing before leaving the island, but of course were also observing whatever nature we could.

In that spirit, and while sitting on a deck on the west side of the island and looking at a mudflat (in between swatting sand gnats), we noticed a seagull flying about 10 meters (>30 feet) above a wooden pier. At one point, it paused its ascent, and we saw an object fall from its mouth and down toward the pier. Thunk! We clearly heard the impact of the object correlate with what we saw, and with much excitement realized that we had just witnessed seagull clam-cracking for the first time.

A mudflat replete with mud snails (probably Ilyanassa obseleta), grazing away and making gorgeous meandering trails on the western side of Jekyll Island (Georgia). But wait, what are those big white chunks on the same surface?

A mudflat replete with mud snails (probably Ilyanassa obseleta), grazing away and making gorgeous meandering trails on the western side of Jekyll Island (Georgia). But wait, what are those big white chunks on the same surface?

Why, look at that: hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) in an unnatural state, i.e., disarticulated, broken, and dead on the surface of the mudflat. These clams normally burrow into and live under the mud, and usually manage to stay intact if they stay below the surface. The pieces of clams here must have bounced off the wooden pier, which is casting a shadow in the lower right-hand side of the picture. (Both preceding photographs by Anthony Martin and taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Why, look at that: hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) in an unnatural state, i.e., disarticulated, broken, and dead on the surface of the mudflat. These clams normally burrow into and live under the mud, and usually manage to stay intact if they stay below the surface. The pieces of clams here must have bounced off the wooden pier, which is casting a shadow in the lower right-hand side of the picture. (Both preceding photographs by Anthony Martin and taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

What was most surprising to me about this broken-shell assemblage on the pier was how it was represented only by the hard clam, or quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria). These thick-shelled clams are quite common in sparsely vegetated muddy areas of salt marshes, burrowing into the mud and connecting their siphons to the surface so that they can filter out suspended goodies in the water during high tides. During low tides, however, they become vulnerable to avian predation. Despite being “hidden” in the mud, somehow the seagulls spotted them from the air, landed next to them on the mudflat, and pulled them out of the mud. They then used the nearby pier as an anvil, and the clam’s hard, thick shell unwittingly became its own hammer when they hit the pier after falling from a fatal height.

The horror, the horror: a clam killing “ground,” thoughtfully supplied by humans for seagulls in the form of a long, hard, wooden pier. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter and Yours Truly for scale, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The horror, the horror: a clam killing “ground,” thoughtfully supplied by humans for seagulls in the form of a long, hard, wooden pier. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter and Yours Truly for scale, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

OK, now it’s time to think about broken clams and deep time. If you found such an assemblage of broken shells of the same species of thick-shelled clams in a geologic deposit, how would you interpret it? Would you think of these broken shells as predation traces, let alone ones made by birds? Which also prompts the question, when did seagulls or other shorebirds start using flight and hard surfaces to open clams? Did it evolve before humans, and if so, was it passed on as a learned behavior over generations as a sort of “seagull culture”?

All of these are good questions paleontologists should ask whenever they look at a concentration of broken fossil bivalves that are all of the same species, and overlapping with the known geologic range of shorebirds. In short, these may not be “just shells,” but evidence of birds using gravity-assisted killing as part of their predation portfolio.